Follow-up to 'GitFlow considered harmful'

This post is part of a series of articles on working with the Git source control system.

- GitFlow considered harmful

- Follow-up to 'GitFlow considered harmful'

- OneFlow – a Git branching model and workflow

- Implementing OneFlow on GitHub, BitBucket and GitLab

My previous post, in which I explained what I disliked about GitFlow, generated a lot of feedback on /r/programming, HackerNews, Twitter and in the comments section of the article itself. I like to thank everybody who took the time to read the post and maybe write a response – it’s been great knowing that a lot of you have had similar experiences to mine, and even better finding out that for some people, those things that bug me are not a problem at all (I devote a whole section to that issue below).

While reading and responding to the comments, there were a few cases where the same issues would keep popping up again and again, which indicates to me that I did not make myself clear enough in a couple of places. In this post, I attempt to clarify those recurring issues.

“I agree with the article, but we have to keep using GitFlow because your workflow can’t do X”

The workflow I described can do everything that GitFlow can. I am absolutely positive of this, and I know it from experience. I think when I wrote that it’s simpler, some people took it to mean that it’s a trimmed down version that sacrifices some of the features to achieve that simplicity. That is not the case; it’s simpler, but exactly as powerful as GitFlow with regards as to how expressive the branching model is. That’s why I can say with confidence that’s it strictly superior to GitFlow – you can retain the same basic way of doing things as you had before, it will just be easier.

There is a particular case of this issue that I want to address in a separate point:

“The master/develop split is needed so we can bugfix the current production version”

I think my mistake here was assuming that everybody was familiar with the terminology surrounding this issue. The name that GitFlow, and my article, uses for these kind of bugfixes is ‘hotfix’, and it’s very easy to do with one eternal branch, because each release of the software is tagged with the version number. I’ll explain the process again on a concrete example, illustrating the various points with diagrams.

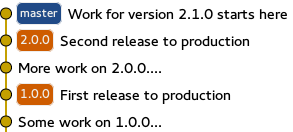

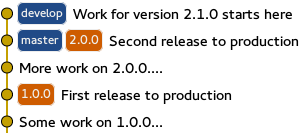

Let’s say the last production release of some example project that we’re working on was version 2.0.0, and currently work is underway on version 2.1.0. This work-in-progress on the next release is, of course, happening on master, so the situation is as follows:

(Some people were curious what is the GUI client I’m using for these images. It’s gitg, as I’m on Linux. It’s funny that even though Git started as a natively Linux application, Linux has by far the worst GUI clients for it of all the major platforms)

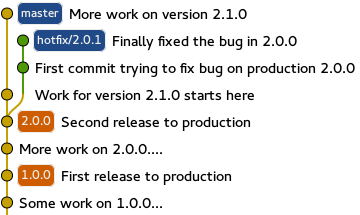

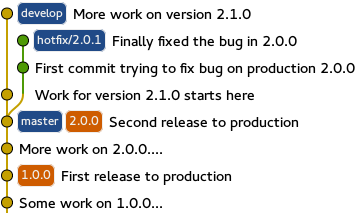

And now, disaster strikes – somebody finds a critical bug in the 2.0.0 version on production, and it needs to be fixed ASAP. Obviously, the fix should not include all the current work-in-progress on version 2.1.0 that is happening on master at this point. What do you do? You create a new branch, hotfix/2.0.1, which starts at the commit pointed to by tag 2.0.0, and you fix your critical bug on that separate branch. Let’s say it took you two commits to do that. Now the situation looks like this:

Notice in particular that work-in-progress on version 2.1.0 continued as normal on master (the “More work on version 2.1.0” commit) during the whole time that the bugfixing was going on. The two do not interfere with each other in any way.

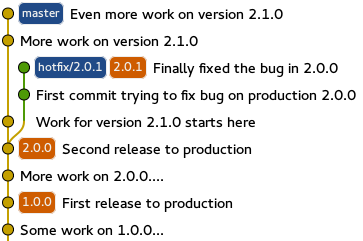

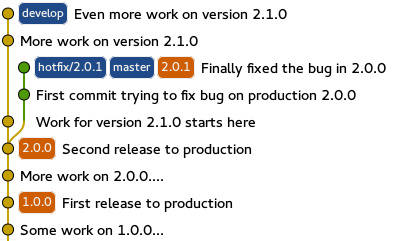

So your fix gets deployed in the test environment, QA takes a look at it and everything seems to be OK. Now it’s time to deploy it to production. You tag the tip of the hotfix/2.0.1 branch with version 2.0.1 (obviously) and do the release as you normally would. The situation is then:

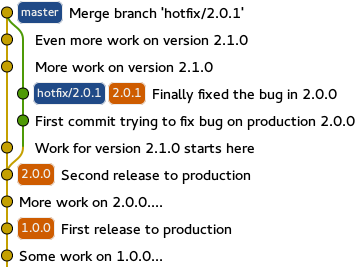

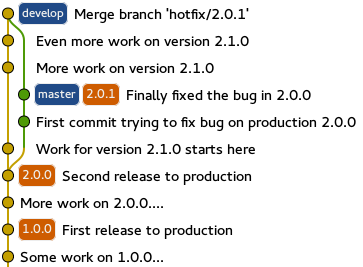

Again – none of this impacts work that is still going on on master for version 2.1.0 (commit “Even more work on version 2.1.0”). So, the release is done, and production is on version 2.0.1. The only thing that’s left to do is to make this change versioned permanently. Since there’s only one eternal branch in our repository, there’s only one possible way this can be done: merge the hotfix to master. Which makes the history look as follows:

At this point, every commit reachable from hotfix/2.0.1 can be reached also from master, so this branch contributes nothing to history. After hotfix/2.0.1 is deleted, the bugfixing is considered closed.

EDIT: as RobM helpfully points out in the comments, note that deleting the hotfix/2.0.1 branch does not affect the tag 2.0.1 in any way – in particular, it’s not deleted.

Some additional notes on this subject:

- This procedure can be applied as many times as you need. For example, if there was a bug found in version

2.0.1, you would create a branchhotfix/2.0.2starting at tag2.0.1. - Doing regular releases (that is, non-hotfixes) is very similar to this. The difference is the name of the branch (

release/2.1.0instead ofhotfix/2.0.1) and the starting point (it’s the commit on master that you determine includes all of the features you want to incorporate into this particular release instead of the currently released version tag, like in the case of a hotfix), everything else is exactly the same. - Notice that hotfixes and regular releases change different version numbers. If you use Semantic Versioning, releases change either the major or minor number (depending on the scope of the changes that that particular release introduces), while hotfixes change the patch number. This way you know how many hotfixes were there in a given release cycle just by looking at the version (for example, if production is currently on

3.2.5, that means3.2.0had to be hotfixed five times).

I hope this explanation makes it clear that you in fact do NOT need separate eternal branches in order to isolate changes to a current production release.

“I can’t delete my release branches”

This is another case of a terminology misunderstanding. The concept of a release branch has a very specific meaning in GitFlow, and I used it in the same way in my article. It’s a short lived branch that is used for work preparing a SINGLE release (and it’s named after that specific release number, for example, release/1.2.3). The assumption that GitFlow (and thus my workflow) makes is that this branch can be short-lived, because changes on it are always merged back to the mainline. In other words, every new release is based on all the previous ones (to put in yet another way, all of the previous release commits are ancestors of the new release commit in the Git repository).

Now, a lot of people use the term ‘release branch’ differently. This happens mostly when that assumption (that each new release is based on all of the previous ones) is not true in their situation. The most common scenario when that occurs is when you have to maintain completely separate versions of the same project in one repository. Imagine, for instance, that you sell your software to individual clients, and each of them has different customization needs that they order from you. Obviously, you need to maintain separate versions of the project to keep providing those customizations, but at the same time those released versions can’t be based on all the previous ones, because that would mean customizations meant for different clients get mixed up with each other.

When the repository looks like that, people often call the branch keeping the code version for a particular client a ‘release branch’ (since this is the branch that a release for a particular client is made from). The most important thing to realize is that if that’s how you work, you aren’t using GitFlow (because of the failed assumption I mentioned), and so my post doesn’t really apply in your situation. Maintaining completely separate versions of a project is a tough problem that doesn’t really have an easy solution, and I won’t pretend I have one. Just remember that my workflow can’t really be used in this case (and naturally, neither can GitFlow).

“You have to look at tags to get the latest production version”

A lot of people complained that using the workflow I described, in order to reach the state of the last release in the code, you have to look at tags and choose the latest one, while in GitFlow you just did git checkout master. While that is true, if it’s something that is important to you, it’s a very easy problem to solve.

You create an additional branch, you can call it ‘current’ (or whatever else you want, but I’ll use ‘current’ in this description), whose only purpose is to point to that latest tag. The workflow is exactly the same, except whenever you do a hotfix or a release, there’s one extra command you need to execute: git merge <new_tag_name> while on the ‘current’ branch, which simply fast-forwards this branch to the newly created production version. This way, ‘current’ can always be checked out to reach the latest production release.

When people heard about this, they complained (rightly so, I think) that for open-source projects, you usually want ‘master’ to play the part of the latest released version. That’s true, and what’s beautiful about Git is that branch names don’t matter. So you simply rename ‘current’ to ‘master’, and ‘master’ to, let’s say, ‘develop’.

To avoid any more misunderstandings, I’ll now show you the same diagrams I used to illustrate the hotfix workflow, but with the branch names changed according to this scheme.

Before the bug is discovered:

After the bug is fixed, but not released yet:

After the fix is released to production, but before the hotfix is merged:

After the fix is merged and the branch hotfix/2.0.1 deleted:

Remember, all we changed was we renamed what was previously called ‘master’ to ‘develop’, and introduced another branch pointing at the latest tag. That is all; everything else stayed exactly the same as it was before.

“WAIT!”, I can almost hear you say, “You JUST said in the other article that the master/develop split is redundant! And now you’re using it yourself? What the hell is up?!”. Let me explain.

First of all, that comment was made strictly in the context of how GitFlow uses the master and develop branches. I never said keeping more than one eternal branch NEVER makes sense – for instance, I said you need to do it in the previous section, when I talked about maintaining different versions of the same project in one repository. It’s this PARTICULAR master/develop split that sucks – not EVERY master/develop split.

Secondly, this is a totally different way of using master than how GitFlow does it. Notice that master is never committed or merged to directly – the only way it changes is it’s fast-forwarded to a commit already in the repository. To put it in another way, there is never a point in time that master points to a commit that’s not reachable from another branch or tag in the repository (contrary to how it works in GitFlow). It’s never used in the day-to-day work of developers, and doesn’t affect their workflow in any way (the only person who’s affected is the one doing or scheduling the release). It’s nothing more than a convenience to make reaching the production release of the project quicker. That’s why in the comments of the previous post, I referred to it as a “marker” branch – a branch whose sole purpose is to point to a particular commit. You can think of it as a mutable tag. Again, to reiterate – this is NOTHING like the master from GitFlow.

And lastly, you can actually argue that master IS in fact redundant in this scheme. It duplicates information that’s already accessible through tags. The difference between GitFlow’s redundancy is that this redundancy has a clear purpose – to make it easy for people who are cloning the repository for the first time to reach a stable state of the project.

“The workflow you described won’t work with our CI setup”

I hope the previous section adressed these concerns as well. After all, you can have master & develop this way, which is exactly what GitFlow has, so there should be no difference between them.

I hope the previous section illustrated how easy it is to customize this workflow to fit your particular needs. For example, I can imagine adding another marker branch, called ‘prev’, which tracks the previously released production version – which can be used to quickly roll back a release if it turns out the current one is broken.

“You make good points, but I still prefer merging over rebasing”

Some people, when faced with choosing between the merge spaghetti and the linear history that I presented, said they actually prefer the former. There is nothing I can really do to convince them at this point. If that’s how they prefer it, then I think there’s no other way forward than to accept the apparent fact that different people have very different ways of using and searching the history of a Git repository.

If you remember, in my description of the workflow I said that you have a lot of leeway in how adamant you want to be in enforcing linear history. This means, in particular, that you can choose not to do it at all, and keep using the --no-ff flag. And that’s OK; the workflow will still work, exactly like it was described.

The debate whether to merge or rebase feature branches is old, and not one I expect will be settled soon. I’m firmly in “Team Rebase” (hmmm, that gives me an idea for a T-shirt…) – that’s how I work every day, and it’s absolutely natural to me. I won’t waste time trying to convince you, if you prefer merging. The best argument I’ve ever seen in favor of rebasing was actually made in the HackerNews thread discussing the previous post. You can read it here. If that doesn’t convince you, I for sure won’t.

A nice compromise that was suggested multiple times by various commenters was a hybrid approach. Basically, after you’ve finished your work on the feature branch (meaning, at the point you would do a --no-ff merge in GitFlow), you first delete the remote branch (if there was any), then rebase your changes on top of develop, simultaneously cleaning up the history (correcting commit messages, squashing some commits into one etc.), and only then do a merge with --no-ff. This way you can have the best of both worlds: nice, almost linear history that you get with rebases and good separation and ease of rollback that merges afford you. I agree that this is a very cool approach; the only thing that bothers me about it is I don’t know of any way of enforcing it.

The main point I’m trying to make is this: even if you don’t agree with me about rebases, merges and --no-ff, the rest of the arguments I make should remain valid, and you can still use the workflow I described, and use it more effectively than GitFlow.

Summary

I hope this article clears up some of the confusion that I may have caused by not being precise enough in my previous post. If there’s still something that is unclear to you, please let me know in the comments, and I’ll try my best to clarify it further.

This post is part of a series of articles on working with the Git source control system.

- GitFlow considered harmful

- Follow-up to 'GitFlow considered harmful'

- OneFlow – a Git branching model and workflow

- Implementing OneFlow on GitHub, BitBucket and GitLab