GitFlow considered harmful

This post is part of a series of articles on working with the Git source control system.

- GitFlow considered harmful

- Follow-up to 'GitFlow considered harmful'

- OneFlow – a Git branching model and workflow

- Implementing OneFlow on GitHub, BitBucket and GitLab

GitFlow is probably the most popular Git branching model in use today. It seems to be everywhere. It certainly _is_ everywhere for me personally – practically every project at my current job uses it, and often it’s the clients themselves who have chosen it.

I remember reading the original GitFlow article back when it first came out. I was deeply unimpressed – I thought it was a weird, over-engineered solution to a non-existent problem. I couldn’t see a single benefit of using such a heavy approach. I quickly dismissed the article and continued to use Git the way I always did (I’ll describe that way later in the article). Now, after having some hands-on experience with GitFlow, and based on my observations of others using (or, should I say more precisely, trying to use) it, that initial, intuitive dislike has grown into a well-founded, experienced distaste. In this article I want to explain precisely the reasons for that distaste, and present an alternative way of branching which is superior, at least in my opinion, to GitFlow in every way.

GitFlow’s mistakes

So what is it that irritates me about GitFlow so much?

It makes the project’s history completely unreadable

The absolutely worst part of GitFlow is this advice:

Finished features may be merged into the develop branch [to] definitely add them to the upcoming release:

(…)

$ git merge --no-ff myfeature(…)

The

--no-ffflag causes the merge to always create a new commit object, even if the merge could be performed with a fast-forward.

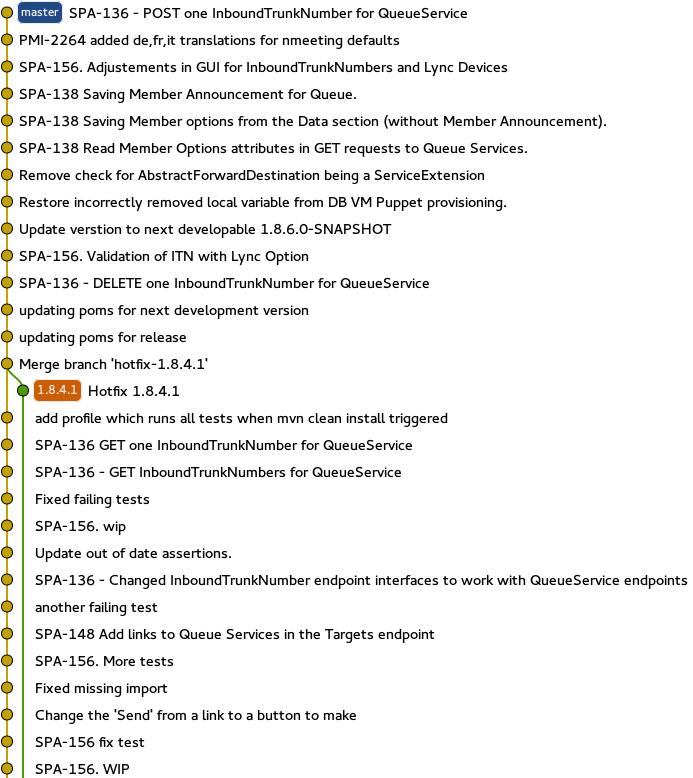

This paragraph alone caused more damage than the other parts of the article combined. Because of this “advice” (which is presented as some absolute and obvious truth, when in fact it’s nothing more than an opinion-based convention, and an unpopular one at that), the history of a project managed using GitFlow for some time invariably starts to resemble a giant ball of spaghetti. Try to find out how the project progressed from something like this:

This isn’t the worst mess I’ve seen as a result of applying GitFlow principles – far from it, actually. I just grabbed the first example I could get a hold of easily – this screenshot captures a recent state of a project I’m currently involved in. Finding anything in a history looking like that is close to impossible. And this is from a small team (~7 developers) – imagine how much worse would it look for a larger one. The author of GitFlow said he uses it in his personal projects. Perhaps he just never had to scale this approach, and thus never realized that the created mess would increase exponentially with each new team member. Or maybe he just never had to search for something in the intangible maze that GitFlow makes of your project’s history.

(As an aside, this screenshot also captures a rather hilarious mistake in versioning – which tend to happen quite often when trying to use GitFlow, as I mention below. If you think you’ve found it, let me know in the comments!)

Fortunately, people have caught on pretty quickly that these merge commits everywhere are maybe not that great of an idea as it was presented, and virtually nobody heeds the advice about the --no-ff flag anymore (at least in my experience). Unfortunately, the damage in the mentality of the users has already been done – they have been conditioned to think that simple, linear history is somehow inferior and less “professional” than this merge-commit hell, and are discouraged from learning and using things like cherry-picking and rebasing – because a messy history seems inevitable to them (or, even worse, it starts being actually desirable, to inflate the perceived difficulty of the project and their work – again, they want to appear “professional”). What is more, because of an unnecessarily large amount of branches used in GitFlow (see below), there are still a large number of merge commits cluttering the history.

The rationalization that the original article uses for always creating this merge commit is also somewhat dubious to me. To quote:

In the latter case [without

--no-ff], it is impossible to see from the Git history which of the commit objects together have implemented a feature — you would have to manually read all the log messages.

Right. Except the only way to find that merge commit created by the --no-ff flag is by, you know, manually reading all the log messages. So what is the gain from this approach is beyond me.

If you’re still unconvinced, let me illustrate my point with a concrete example. Let’s say that you’re working on the project whose history was shown in the image above, and there’s a problem with the code changed while working on issue SPA-156. Which history would you rather be faced with when investigating this problem – the one shown above, or this one?

The master/develop split is redundant

GitFlow advocates having two eternal branches – master and develop. Why two, when one is the conventional standard? After using it for one year, I still have no idea. What is more, I am now certain that there is nothing gained by having two branches instead of one. Let me quote the original article again:

When the source code in the develop branch reaches a stable point and is ready to be released, all of the changes should be merged back into master somehow and then tagged with a release number. How this is done in detail will be discussed further on.

Therefore, each time when changes are merged back into master, this is a new production release by definition. We tend to be very strict at this, so that theoretically, we could use a Git hook script to automatically build and roll-out our software to our production servers everytime there was a commit on master.

If you analyze these two paragraphs closely, I think you will agree with me: the master branch contributes nothing to the history. Think about it: if every commit to master is a new release from the develop branch, and every commit on master is tagged, then you have all of the information you would ever need in that develop branch and those tags. At this point keeping master around accomplishes nothing of value.

What this does accomplish, however, is create more useless merge commits that make your history even less readable, and add significant complexity to the workflow. Which brings me to my final, and biggest, gripe with GitFlow.

It’s needlessly complex

All of these branches that are used force GitFlow to have an elaborate set of complicated rules that describe how they interact. These rules, coupled with the intangible history, make everyday usage of GitFlow very hard for developers.

Can you guess what happens whenever you set up a complex web of rules like that? That’s right – people make mistakes and break them by accident. In the case of GitFlow, this happens all the time. Here is a short, by no means exhaustive list of the most common blunders I’ve observed. These are repeated constantly, sometimes every day, often over and over again by the same developers – who are, in most cases, very competent in other software areas.

- Reverting somebody else’s changes because of conflicts happening during a merge and the inability to find the correct version in history

- Confusing to which branch should a change be actually pushed (this happens so often it might be called a “standard” mistake)

- Starting a support branch from the wrong initial branch, or finishing a support branch by merging to the wrong final branch

- Forgetting to tag a release (cause there was a commit on master, right?), and so then accidentally changing the release in place, instead of creating a new one

- Not building the actual release from the commit that is later tagged with the (supposed) release number

You could of course say that all of these mistakes are the result of human error, and if the same people just read the documentation and learned from their experiences, everything would be fine. But I have seen these mistakes being made so many times, by otherwise competent developers, that I don’t buy this argument. There’s a saying I love: “If one person tells you you have a tail, ignore them; if a hundred people tell you that, look behind you”. If these mistakes happen over and over again (and I can confirm based on my experience that they do), made by different people in different circumstances, then there’s no rational alternative to admitting there has to be something fundamentally flawed about the method being used.

But mistakes aren’t even the worst part. What I consider the biggest failure of GitFlow is that it doesn’t give people a clear vision of a versioning scheme. This is especially true if you have any deviations from the standard workflow that GitFlow forces on you (for example, you have a long release cycle with a lot of back and fourth between QA and development). All of the mistake examples I gave above really stem from the fact that people are confused about what actually represents the current state of the project. Since they don’t really understand what that state is, then it’s no wonder that they make mistakes when they try to change it (as that is what publishing their work is actually meant to accomplish).

Anti-gitflow

“OK, smartass”, I can imagine you thinking, “If GitFlow is so bad, what do you propose we use instead?”. I’m glad you asked. I want to describe an alternative method that I’ve used myself successfully on a number of projects (to be clear, I’m not talking about one-person projects). I believe it fulfills all of the goals that GitFlow set out to accomplish, and does it in a lot simpler, clearer and lightweight way which scales to any number of developers. You can call it “Anti-gitflow”, as it’s very similar in a lot of points that don’t need any change compared to GitFlow, but does the exact opposite wherever GitFlow falls short, as I’ve described above.

Here it is:

- There is only one eternal branch – you can call it master, develop, current, next – whatever. I personally like “master”, and that’s the name I’ll use in the rest of the description, as it’s convention by now in the Git world and immediately conveys its purpose.

- All other branches (feature, release, hotfix, and whatever else you need) are temporary and only used as a convenience to share code with other developers and as a backup measure. They are always removed once the changes present on them land on master.

- Features are integrated onto the master branch primarily in a way which keeps the history linear. You have a lot of leeway in how you want to enforce this. You can make it simply a convention that developers are encouraged, but not forced, to follow. On the other side of the spectrum, if you use something like Gerrit to manage your Git repositories (which I recommend, even if you don’t practice code reviews – the permission system is fantastic, and if you ever decide you want code reviews, it’ll be very easy to start doing them), you can set up permissions in such a way that actually forbids pushing merge commits to master, and that way ensure linear history.

- Releases are done similarly to in GitFlow. You create a new branch for the release, branching off at the point in master that you decide has all the necessary features. From then on new work, aimed for the next release, is pushed to master as always, and any necessary changes are pushed to the release branch (in my opinion, it’s an anti-pattern and a huge red flag if your release requires separate commits to work, but that’s a topic for another article – for simplicity, let’s assume you can’t or don’t want to change that). Finally, once the release is ready, you tag the top of the release branch. Then, because there is one eternal branch, there is only one way to get your release to be versioned permanently – and that is to merge the release branch into master and push that changed master. After that, all the changes that were made during the release are now part of master, and the release branch is deleted.

- Hotfixes are very similar to releases, except you don’t branch from an arbitrary commit on master, but from the release tag that you want to make the fix in. Again, work on master continues as always, and the necessary fixes are pushed to the hotfix branch. Once the fix is ready, the procedure is exactly the same as for a release – tag the top of the branch creating a new release, merge it into master, then delete the hotfix branch.

(For a more detailed description of this workflow, see the “OneFlow – a Git branching model and workflow” article)

As you can see, this workflow is quite similar to GitFlow, but tries to avoid its pitfalls mentioned earlier. Linear history makes merges and/or rebases easier, while having only one eternal branch takes away a lot of the complex rules. The state of the project is clear – the top of master is what will be in the next release, and the latest tag is what is on production. This workflow, even though it’s simpler, loses nothing in terms of expressiveness of how the project’s history is managed compared to GitFlow – on the contrary, the history is more useful, because encouraging keeping it linear makes it that much easier to search.

Moving forward

I hope I wasn’t too critical of the author of GitFlow in this article. That certainly wasn’t my intention. He simply shared a way of using Git that worked for him and his team(s) with the rest of the world, thinking that others may find it useful. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that. His approach does contain some sound ideas. However, I also believe that GitFlow is fundamentally flawed in many aspects, and my experiences of observing people trying to apply it only confirm that impression. And because there is a simpler, equally (or, I would even argue, more) expressive way to manage your project’s history, I don’t see a reason to ever use GitFlow anymore.

This post is part of a series of articles on working with the Git source control system.